Ed. note - in the below "disappeared" is known in Latin America as "Desaparecido" - which see.

| Guatemala, Ríos Montt And The SOA |

| TUESDAY, 13 MARCH 2012 19:24 |

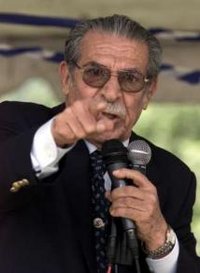

By: Nick Alexandrov  Three decades after José Efraín Ríos Montt finished his coursework at the U.S. Army School of the Americas (SOA)—where tens of thousands of Latin American soldiers have been trained in the art of violent repression; it was renamed the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation (WHINSEC) in 2001—he seized power in Guatemala, and then ripped its social fabric to shreds. “During the 14 months of Ríos Montt’s rule, an estimated 70,000 unarmed civilians were killed or ‘disappeared;’ hundreds of thousands were internally displaced,” according to Amnesty International. In the summer of 1982, he launched “Operation Sofia,” which destroyed 600 Mayan villages. Three decades after José Efraín Ríos Montt finished his coursework at the U.S. Army School of the Americas (SOA)—where tens of thousands of Latin American soldiers have been trained in the art of violent repression; it was renamed the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation (WHINSEC) in 2001—he seized power in Guatemala, and then ripped its social fabric to shreds. “During the 14 months of Ríos Montt’s rule, an estimated 70,000 unarmed civilians were killed or ‘disappeared;’ hundreds of thousands were internally displaced,” according to Amnesty International. In the summer of 1982, he launched “Operation Sofia,” which destroyed 600 Mayan villages. Had Ríos Montt lived centuries ago, he might be remembered as a hero today. We can compare him, for example, to the Admiral who, as scholar David Stannard recounts, on one campaign “set forth across the countryside, tearing into assembled masses of sick and unarmed native people, slaughtering them by the thousands.” That was Columbus on Hispaniola, back in March 1495. Or perhaps Ríos Montt is a worthy successor to the man the Iroquois dubbed “Town Destroyer” in the 1770s. Historian Robert A. Ferguson relates the words of Seneca Chief Cornplanter: “When that name is heard, our women look behind them and turn pale, and our children cling close to the necks of their mothers.” The Indians were referring to George Washington. But killers of this caliber today face challenges their predecessors never confronted. For the past several decades, groups of activists in the U.S. and especially Latin America have brought attention to Washington-backed terror campaigns in countries like Guatemala, winning a major victory this past January 26, when “Judge Carol Patricia Flores Blanco ruled…that there was sufficient evidence linking Ríos Montt” to human rights violations for him to “face trial on genocide and crimes against humanity,” Rory Carroll reported in the Guardian. Horrific as Ríos Montt’s crimes are, we should bear in mind that his policies were fundamentally in line with those of the Guatemalan officials running the country both before and after his term in office, as well as in close conformity with Washington’s longstanding goals for the region. During World War II, U.S. State Department planners wrote frankly of the “problem,” as they saw it, with “the other American republics,” which were “manifesting an increasingly strong spirit of independence and jealous insistence on complete sovereignty.” This nuisance presented difficulties in light of, say, Washington’s efforts to ensure it would be granted “long-term rights for the use…of certain naval and air bases in the other American republics,” and its wish “to maintain the economies” of Latin American nations in accordance with its principles—“quite apart from equity, it is to the selfish interest of the United States” to do so, planners emphasized. Just as these policies were taking shape, Guatemala entered what was, from the U.S. government’s perspective, a decade-long crisis. In 1944, a popular revolt brought down Jorge Ubico, the dictator Washington supported. His successor, Juan José Arévalo, won overwhelmingly in the election held that December; while in office, he started democratizing the country. Jacobo Arbenz followed as president in 1951, and a year later passed the Agrarian Reform Law, with which the government gained the power to expropriate idle land—most of the United Fruit Company’s, for example. This law fit in with Arbenz’s broader strategy, which was to limit the power of the major companies for which Ubico had created an ideal business climate, generally the sort of environment in which corporations are treated like people in need of nurture, and “human lives are so much trash,” to borrow the poet Charles Olson’s formulation. Under Ubico, Susanne Jonas explains in The Battle for Guatemala, the government was “active…in protecting and subsidizing (but never regulating or restricting) private enterprise;” it also repressed most of the population, keeping workers poor, terrified, and atomized—and profits high. But ultimately it was Guatemala’s “increasingly strong spirit of independence” under Arbenz, more so than any specific policies limiting United Fruit’s freedom to operate, that led to his downfall in the 1954 CIA coup. With Arbenz out of the picture, the Guatemalan government, acting on U.S. Embassy instructions, began hunting down thousands of perceived subversives, torturing many of them in an effort to terrorize the population back into submission, and to destroy the popular organizations that had begun to form during the brief democratic period. Thus brutalized, the public could do little to protest, for example, the 1955 Petroleum Code, written in English and “a giveaway measure” for foreign companies, Jonas explains. And there were other measures restoring business privileges Arbenz had undermined. Since none of these arrangements would have met with widespread support, the counterrevolution’s task was to ensure immediately that Guatemalans could not influence issues affecting their lives, and then to create a society in which Guatemalans could not even conceive of having such influence—“the United States felt it necessary to root out all traces of progressive politics,” Jonas concludes. To this end, Washington restructured Guatemala’s security forces in the 1960s, doubling the army’s size, and creating the Mobile Military Police, which expanded the state’s reach into rural regions. These changes coincided with U.S. training for counterinsurgency units, both at the SOA and in-country, as when Colonel John D. Webber traveled to Guatemala in 1966 to monitor the new squadrons’ instruction. Despite official rhetoric to the contrary, government repression was “totally disproportionate to the military force of the insurgency,” according to the authors of the 1999 UN-backed Historical Clarification Commission—it was state terror, in plain terms, due to which perhaps 8,000 people paid the ultimate cost between 1966 and 1968. But things weren’t all bad. In 1962, a Chase Manhattan Bank report noted “the more favorable business climate” of the post-Arbenz era, in which foreign investments “will begin to pick up,” its authors had little doubt. Efforts to crush progressive politics intensified in the following years, and were pursued with utter ferocity in the early 1980s. The 1981-1983 period was the one in which “agents of the State of Guatemala, within the framework of counterinsurgency operations”—developed with Washington’s help, it cannot be overemphasized—“committed acts of genocide against groups of Mayan people,” according to the 1999 truth commission. These were the years when Ríos Montt was largely running the show, with the help of his cabinet, two-thirds of whom—like the dictator himself—were SOA alumni. Documents from “Operation Sofia” (the code name for the genocidal assault on Mayan communities) on the National Security Archive website demonstrate that this policy’s planning and direction were carried out at the highest levels of the Guatemalan government. In Guatemala: Nunca Mas!, the report issued by the the Guatemalan Archdiocese’s Human Rights Office, we get a sense of what this “more favorable business climate” was like. One testimony recalls “burned corpses, women impaled and buried as if they were animals ready for the spit, all doubled up, and children massacred and carved up with machetes.” Another described how soldiers tied up a family inside a house, and then torched it; a two-year-old was among those burned to death. Yet another tells how a pregnant woman “in her eighth month” came face-to-face with counterinsurgency forces: “they cut her belly, and they took out the little one, and they tossed it around like a ball.” And in 1980, after shooting a woman lame, a group of “soldiers left their packs and dragged her like a dog to the riverbank. They raped and killed her.” These are just four examples of thousands, and part of the broader policy of brutalization for which, in particular, Defense Minister Héctor Gramajo Morales bore major responsibility. In recognition for his efforts, he was honored at the SOA’s December 1991 commencement exercises in Fort Benning, GA; he also received a Mason fellowship to study at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government, a safe haven for other contributors to the cause of Guatemalan genocide denial. Samantha Power, who taught there before Obama tapped her for his National Security Council, did not even bother to mention Guatemala in her Pulitzer-Prize winning “A Problem from Hell”: American and the Age of Genocide, perhaps one reason for her image, at least in the New York Times’ world, as a “fiercely moral” figure. Again and again in the history sketched out above, we see that Washington’s goal was to destroy, and then prevent from re-emerging, Guatemalan democracy. In this aim it largely succeeded. We also see that officials in the U.S. and Guatemala assumed that neither Guatemalan officers nor their U.S. trainers were to be punished for participating in mass slaughter; impunity reigned, and attempts to face the past honestly provoked panicked responses. In 1998, for instance, Bishop Juan José Gerardi, one of the key figures behind Guatemala: Nunca Más!, was murdered two days after presenting the report in the Guatemala City Cathedral. His killers pummeled his face with a concrete slab, mutilating it beyond recognition. Colonel Byron Disrael Lima Estrada was one of three men responsible for the attack; his CV, according to the National Security Archive, “reads like a guide to a career in repression,” not least because of his training at the SOA. Other activists carried on the bishop’s work, and it was only because of their efforts that basic moral principles have recently been applied to Guatemala’s criminal ex-rulers. Now, as a result of decades of human rights efforts, Ríos Montt and others may be forced to take responsibility for their actions. But while activists have made progress on these fronts, in many regards the majority of Guatemalans still suffer from the legacy of the 1954 coup, and subsequent governmental assault. In an article for the Guardian last spring, Felicity Lawrence pointed out that while Guatemala produces plenty of food, most of it is sent out of the country in accord with an IMF agro-export plan imposed in the 1980s, leaving half of all children under 5 malnourished—the same percentage of the population that lives in extreme poverty. Oxfam director Aida Pesquera summed up the key issues: “The food’s here but the main problem is distribution. Land is concentrated in very few hands. The big companies pay very little tax. Labor conditions on plantations are appalling.” In short, it is as if Arbenz never existed. Meanwhile, mining companies thrive as Guatemalans starve. Operating within the Central American Free Trade Agreement’s framework of expansive investor and corporate rights, these businesses have hired private security teams to help maintain the climate Chase Manhattan Bank lauded half a century ago. In the current iteration, this means that Idar Hernández Godoy, secretary of the banana workers’ union SITRABI, was shot to death last year for his organizing efforts. Lawrence reported that plantation laborers, or at least those not too terrified to talk about their work conditions, “said that joining a union was a sackable offense that would lead to blacklisting,” and that work with poisonous agrochemicals—without protective clothing—was becoming increasingly common. This was the situation in Guatemala when Otto Pérez Molina, SOA graduate, was elected president late last year. As an army major in the 1980s, he was stationed in the Ixil region when 70-90% of its villages were destroyed. His personal history, and the history of SOA graduates in Guatemala generally, indicates the country’s future may remain dark—unless something is done about it. Next month, School of the Americas Watch (SOAW) will hold its Days of Action in Washington, D.C., from April 14-17. The organization has been working for over twenty years not only to close the School, but more broadly to draw attention to, and then undermine, U.S. militarism in Latin America. Planned events include a conference from April 14-15 on continuing repression in countries like Guatemala, Honduras and Colombia, and activist strategies for change; two days devoted to direct action and lobbying will follow. More information can be found at soaw.org. It is only through a massive, collective effort that we can ensure, first, that Ríos Montt and others will not escape unblemished into history the way men like George Washington have; and second, that the institutions that enhance and benefit from heartless repression become a distant memory. |

Copyright © 1998 - 2012 SOA Watch: Close the School of the Americas.

No comments:

Post a Comment